West Heavens at 4th Guangzhou Triennial:Memories of Cinema: Mani Kaul/Ranbir Singh Kaleka

Curatorial Statement:

Crossings – Ranbir Kaleka from Avijit Mukul Kishore on Vimeo. (4th Guangzhou Triennial installation view)

India’s contribution to the topic ‘Back to Basics’ puts the focus on celluloid film: a technology intrinsic to the concept of the modern museum. Nothing in the 20th Century died as conclusively as celluloid did. Within a short span of a decade, the prime carrier of the moving image in the world’s largest filmmaking country went extinct. Many thought the cinema too died with the demise of celluloid.

In hindsight, the relatively smooth transition from celluloid to post-celluloid technologies escapes what we could also see as a set of major struggles to keep the celluloid memory alive. To many videomakers in today’s times, the basics of video art lie in the independent cinema movements of the 1970s, 80s and 90s.

This exhibition showcases, together, the rare 1980s and 90s cinema of India’s leading avant garde filmmaker, Mani Kaul (1942-2011) alongside the contemporary video art of Ranbir Singh Kaleka. Kaul is widely considered to have inaugurated the new Indian Cinema in 1969 with his first film, Uski Roti (His Bread). Through the 1980s and 90s he made both several fiction films and a series of non-fiction films that effectively straddle the genres of documentary, travelogue and biography. the present Triennial showcases three of Kaul’s most famous non-fiction films,Arrival (1979), Dhrupad (1982) and Mati Manas (Mind of Clay, 1984), alongside five of Kaleka’s video works, Man With Cockerel (version 1), 2002, Crossings (2005), Fables from theHouse of Ibaan (2007), He Was a Good Man (2008) and Sweet Unease (2010).

Artists and Their Works

Mani Kaul (1942-2011)

India’s leading avant garde filmmaker passed away a month ago, after battling cancer for some years. Kaul was born in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, and graduated from the Film & Television Institute of Inia in 1966, where he was taught by the legendary filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak. He was part of the YUKT Film Collective in the early 1980s. A prominent cultural activist and organiser, Kaul is often named along with Kumar Shahani as a filmmaker seeking to extend the range of Indian film cultures. Ke was a significant teacher to a new generation of film graduates, some of whom became key members of his film unit. Much of his later cinema was strongly influenced by his study of Dhrupad music, which he studied with the legendary musician Ustad Zia Mohiyuddin Dagar. Kaul often worked with a theory of language that he claimed possessed a specific, suggestive dimension beyond its denotative or metaphoric faculties. His elaborate theory of contemporary aesthetic practice, ‘Seen From Nowhere’, was presented in the cultural historian Kapila Vatsyayan’s seminar Inner Space, Outer Space (Indira Gandhi National Centre For Art) and published in the book Concepts of Space: Ancient and Modern. Among various non-Indian sources, has drawn from haiku poetry, the nouveau roman, mannerist painting, Robert Bresson and Yasujiro Ozu.

This is the first time that Kaul’s cinema will be presented in an art museum.

Short Note on the works presented:

Arrival

Film, 19′, 1979

Kaul’s legendary short film was intended as an early statement on the city of Mumbai, the city of migrants into which pour people, goods, food and cattle. The film is a montage of images and sound, and anticipates by some decades the fascination with the city’s street culture merging with its informal economy.

Dhrupad

Film, 74′, 1982

Dhrupad is a film-statement about the form of Dhrupad form of North Indian classical music. Said to have originally proliferated in the Mughal court of Akbar, the form migrated into the several smaller medieval kingdoms of central India. The exploration of the form, associated with spaces, takes place through modern India’s leading exponents of the Dhrupad, Ustad Zia Mohiyuddin Dagar and Zia Fareeduddin Dagar.

Siddheshwari

Film, 90′, 1989

Kaul’s exploration of cinema between fiction ad documentary tracks the life of Siddheshwari Devi (1903-77), a classical thumri singer of the Benares school. The actress Meeta Vasisth performs Siddheshwari, who started singing at the age of 16. The narrative is itself structured like a thumri piece: it presents key motifs (of Siddhi’s life as well as of myths and locations) and elaborates on and around them with different songs, moods, camera movements, etc., until the whole becomes a moving tapestry celebrating the transfiguration of life into music. Shot in colour and monochrome, the film proceeds by means of metaphors, evoked rather than named: an ultramarine boat floats on the Ganges, a dropped

metal utensil produces musical overtones, etc. The intoxicants mandatory to the euphoria of a (sexual) meeting are contrasted with the labour that went into practising the difficult art of music. Towards the end, archive footage of Siddheshwari’s sole TV appearance offers a glimpse of the singer, an image which seems to recede into the technology of the recording until only the eerily intense voice remains.

Ranbir Singh Kaleka

Born in 1953, in Patiala, Punjab.

Diploma in painting at the College of Fine Art, Panjab University.

Masters in painting at the Royal College of Art, London in 1987.

A well known painter, Kaleka moved to video art in the late 1990s with his famous work, Man Threading a Needle (1998-99), which inaugurated the style that he is best known for, that of projecting video upon easel paintings. Kaleka’s style lays bare many of the founding elements what used to be celluloid film: the single frame shot encompassing a span of attention, spaces within and beyond, still characters amid a hyperactive landscape, and thence an interrogation of the very idea of movement. The key elements of Kaleka’s painterly grammar are the oil on canvas: the still work that moves. In moving, it opens up spaces-within-spaces that are straight from the cinema; cinematic sequences mediated by the aura of documentary testimony.

Short note on the works presented

Crossings, 2005

Kaleka’s epic work with four screens. It is spread over four oil paintings upon which four video images play out. The oils themselves comprise isolated individuals, singly, together or in line. These might be refugees or simply bystanders, contemporary figures who come from ‘somewhere else’, surrounded by spaces they don’t know, able to survive only through projecting upon what is around them their memories of the past. Images swirl round them like birds. These are images of windswept mountains, childhood and windmills. A man sits at the end impassively, watching all this.

The key grammar of Kaleka’s work, an oil painting that becomes a moving image, blank spaces that become suffused with projectiles drawn fro memory, are all in evidence here.

Fables from the House of Ibaan, 2007

Kaleka’s extraordinary single-screen image featuring his key dramatis personae: a man, a jug, an interior space, a little boy, a memory screen. The painting comes alive as the painted image of a man blinks. The painted man then stands up, pours from the painted jug, and walks off. The painting appears, as it were, to catch fire, and a boy emerges from the flames. He walks past the standing man, opens a door in the far distance to what could be a second painting, of a woman standing under a tree. The man now walks through the door, as it fills up with a set of documentary tableaux. A woman emerges from behind the man and fills the jug full of milk.

Sweet Unease, 2010

A tryptich with a single projector. Two men (played by the same actor) on two sides of the screen, in two distinct interiors, eat, get up and enter a central space, and wrestle. They leave each other in order to fill up, and again return. Each man leaves his painted self to perform this cyclic act of consumption and violence. The playful energies of the same man, doubled, are expended over a gouged-out wall between the two sumptuous food-lined interiors.

He Was A Good Man, 2008

Video Installation with Single Channel Projection on a 114.3×152.4cm Painting on an Easel

4 minutes 24 seconds loop, 2008

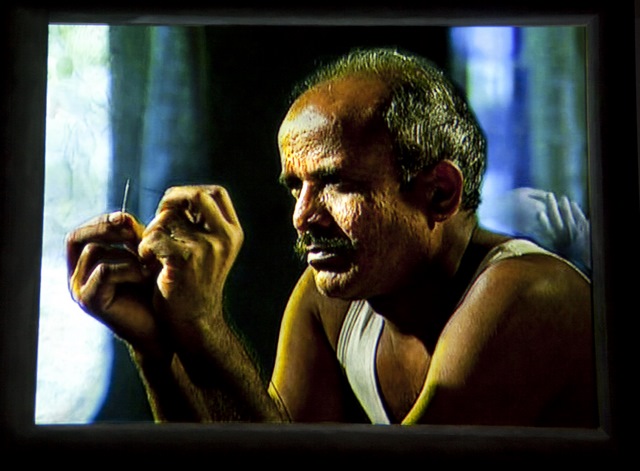

Kaleka’s reworking of his first major video work, Man Threading a Needle. The original painting-that-moved, showing a male figure devoting the greatest attention to that most concentrated of acts – that of pushing a small thread into a miniature hole – had moved minimally. Like the man blinking in the House of Ibaan, the very fact of movement took the viewer back to the origins of movement itself in the moving image. Kaleka’s 2010 remake of that work is almost the opposite of the minimalism of the old: here the full repertoire of Kaleka’s documentary realism, suffused with nostalgic images, is in evidence. The painting / video ends with a door opening and people walking in, to see the painting itself, as if in a gallery.

Man With Cockerel (version 1), 2002

Along with Man Threading a Needle, the second work to explore the most basic of all properties of the moving image. This does not have a painting backdrop. It is in fact a classic example of the earliest of silent cinemas of the cinema, like the Lumiere’s shot of the boy and the hosepipe. A man tiptoes in, tries to pick up a rooster, it flutters in his hands, and he escapes. It is very much like a stray shot from a late silent film jumping, like the cockerel itself, straight into the 21st century. Through the decade, numerous works explore the idea of the tableau, of constructed distance and of the gaze.